Is replication pro-progress or anti-risk?

The role of research integrity in scientific abundance

A core piece of the Abundance and Growth Fund’s work is our grantmaking on science and innovation policy: supporting reforms to make R&D more effective, investing in new scientific models and infrastructure, and funding research on how science works. Replication — independent efforts to reproduce published scientific findings — falls under this umbrella. We’ve supported efforts, like those at the Institute for Replication, to conduct systematic replications of research in important fields; and we’ve worked with experts like David Roodman and Michael Wiebe to check studies that inform our own grantmaking, sometimes finding that they don’t hold up.

But unlike other levers for spurring innovation, replication’s “progress” bonafides are not always clear. How does it fit into our fund’s broader abundance frame?

One argument goes: it doesn’t.

In “Science is a strong-link problem,” Adam Mastroianni writes:

Giant replication projects… also only make sense for weak-link problems. There’s no point in picking some studies that are convenient to replicate, doing ‘em over, and reporting “only 36% of them replicate!” In a strong-link situation, most studies don’t matter. To borrow the words of a wise colleague: “What do I care if it happened a second time? I didn’t care when it happened the first time!”

Adam positions replication among scientific policies and practices that provide a gatekeeping function, which “are potentially terrific solutions for weak-link1 problems because they can stamp out the worst research” but are “terrible solutions for strong-link problems because they can stamp out the best research, too.”

In my work in innovation and metascience, I worry a lot about the proliferation of policies that stamp out the best research; and I worry almost as much about policies that create a thousand cuts of administrative burden despite not branding themselves as gatekeeping. I aim to be a YIMPS (Yes In My Preprint Server) rather than a NIMAJ.2 Are these goals in conflict with our integrity work?

I don’t think so. I believe replication to be a pro-progress intervention, for a few reasons:

Replication provides broad benefits at low cost

Replication isn’t a gatekeeper, it’s a cowbell

Discovery may be strong-link, but translation is not

Replication provides broad benefits at low cost

Not unlike new housing, the pursuit of abundant replication faces the problem of diffuse benefits but concentrated costs. Having one’s work replicated can feel unpleasant. Even if it is not financially costly, there are reputational stakes, indirect incentives to work with the replicator to ensure they are carrying out a comparable procedure, potential back-and-forths to be had via journal comments, etc. Meanwhile, the existence of a replication in your area of study doesn’t feel like much, at an individual level; perhaps a brief “huh, guess that doesn’t hold up” at a lab meeting, followed by a subtle shift of research direction to build on more stable foundations.

But at a system level, producing a few hundred mutterings and a few dozen small shifts in research direction can be incredibly valuable. When a paper is influential and incorrect, it can lead to months- or years-long goose chases that function as a tax on the scientists working in a field, both in time (redirecting their own work away from productive paths) and in resources (redirecting funding and attention away from more promising directions).

In a recent piece for the Institute for Progress, I argued that we can think about the value of replication not as punishment of misdeeds or avoidance of harm, but as a reallocation of resources toward productive science. The strong links that move fields forward arise from researchers building on each others’ work; by pointing a field towards solid foundations, replication can give researchers more opportunities to make meaningful progress.

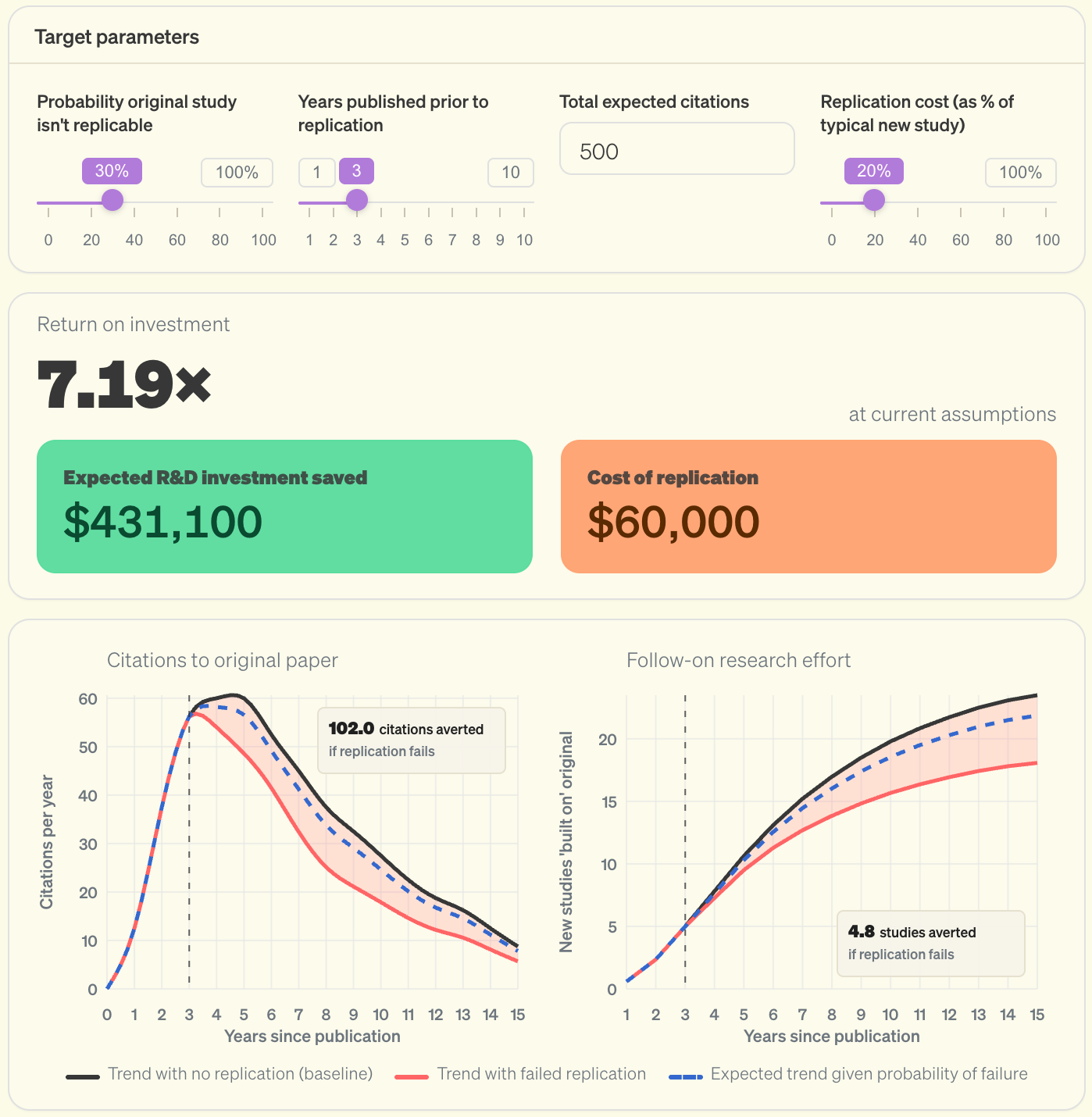

The piece develops an ROI model to understand the potential value of funding replication studies. The ROI depends on a few key factors, including the potential influence of the target paper, how quickly the replication happens, and the cost of the replication. For most papers, replication isn’t worth it. But when targeted at recent, influential studies, replication can pay for itself many times over. In other words, each dollar spent on a well-targeted replication can free up several dollars worth of research effort that would otherwise chase a false lead.3

Importantly, this value comes not from catching cheaters, but from freeing up the time and resources of other researchers. When a failed replication redirects even a fraction of the follow-on effort that would have built on an incorrect finding, those researchers can pursue more promising leads instead.

Replication isn’t a gatekeeper, it’s a cowbell

When I think about scientific gatekeeping, I think about pre-publication interventions that are designed to avoid bad research getting loose in the world. For example, strict peer review, pre-registration mandates, and data management plans achieve their goals by creating hurdles for researchers to jump over before their research can be finalized and shared with the world.

Replication, on the other hand, is less like manning the gate and more like belling the cow. Instead of directly interfering with the production and sharing of scientific outputs, replication latches onto studies that are already in circulation – or are on their way out – and provides an additional information signal to readers that might come across them. And because replication is applied to research in circulation, it can be more easily targeted to the most influential studies,4 ensuring the links that appear strong actually are.

While proliferation of gatekeeping interventions runs the risk of stamping out good ideas, replication may actually be aligned with a more permissive ecosystem, where preprints and papers are allowed to flourish and abundant replication serves as a secondary layer that helps steer resources and identify which links are likely to be strong earlier than we’d otherwise know. Rather than producing thickets of red tape, robust systems for assessing quality and credibility after the fact can decrease the importance of having burdensome up-front systems, allowing for a more streamlined process of knowledge production and sharing.5

Discovery may be strong-link, but translation is not

At a more meta level, I think that while frontier scientific discovery is a strong-link problem, the translation of science to society is not.

Drug development is the canonical example. A paper reporting potential preclinical benefits of molecule X on cell line Y in a specialty journal may not generate substantial follow-on research or advance a broader subfield. But when that genre of paper is incorrect as often as it is correct, preclinical academic literature becomes an unreliable source of leads for biotech startups and pharmaceutical companies, and our system of knowledge translation trades efficiency for redundancy.

Many of us have heard anecdotes that make this concrete: academics who are more valuable to industry for their knowledge of unpublished failures than for the published successes they’ve worked on, or founders who spent years trying to build a startup based on a method that didn’t work the way the paper claimed. In 2012, scientists at Amgen reported that they could reproduce the results of only 6 of 53 “landmark” cancer studies they attempted to validate. Bayer reported similar findings around the same time, successfully replicating only 25% of preclinical projects they took on.

Research on how knowledge flows between academia and industry suggests that this dynamic affects behavior. One study found that when the same discovery is made independently by academic and industry scientists, inventors are 23% less likely to cite the academic paper than its industry counterpart. Interviews with scientists and inventors point to reliability as a key reason.

Across biology, agriculture, materials, policy, even philanthropy, studies that are unlikely to receive much direct scientific attention can still form the backbone of efforts to improve the world. Those results being incorrect will rarely have catastrophic or even visible consequences. But providing additional information on their usability can make it easier and more fruitful for industry, policymakers, and other practitioners to use everyday research as an input to their work, raising the returns of scientific efforts and speeding the pace of innovation.

None of this means there’s never a place for interventions that add up-front burden. Pre-registration of clinical trials for FDA approval is clearly good, even though that policy isn’t supply-enhancing. But replication operates differently, increasing the production, usability, and uptake of good science without adding to the first-order costs. It’s pro-supply rather than anti.

Replicators are welcome in the YIMPS tent.

In Adam's framing, weak-link problems are those where overall quality depends on eliminating the worst performers. Strong-link problems are those where overall quality depends on the best performers. You fix weak-link problems by raising the floor, you fix strong-link problems by raising the ceiling.

Not In My Academic Journal

There is much more detail in the report – including an interactive version of this dashboard, and an estimate of how much of the NIH’s budget could be productively spent on replication – so if you’re eager for more ROI calculations I encourage you to check it out.

The ones where Adam’s colleague did care when it happened the first time!

The FDA’s accelerated approval pathway arguably works on a similar principle, with the use of confirmatory post-market trials facilitating a more permissive approval process.

I agree with you that institutionalized replication can democratize information access about failed replications and thereby forward science because less money and time are waisted pursuing research ideas that others already know won't pan out.

From my own experience in economics research, however, I have one caveat to add on how replication actually might harm great research. I experienced quite often that people talked about a single study that failed to replicate in a single replication study, "ah but that doesn't replicate", as an argument to why one shouldn't do research in that direction. But that's not Bayesian reasoning! I wish there was a more easy/automatic way of communicating the posterior after a failed replication, instead of heuristically ditching an entire new field because of one failed replication...